Notice: Undefined offset: 1 in /var/www/wp-content/themes/jnews/class/ContentTag.php on line 86

Notice: Undefined offset: 1 in /var/www/wp-content/themes/jnews/class/ContentTag.php on line 86

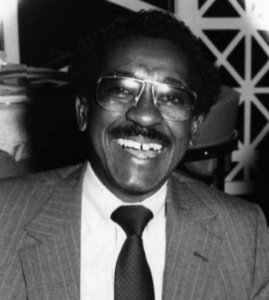

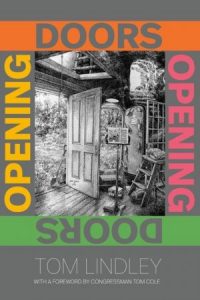

This is an excerpt from the book ‘Opening Doors’, by Tom Lindley. The book chronicles the lives of 13 Oklahoma natives. This chapter details the extraordinary life of Joe Clytus, a black man who overcame racism, discrimination, and Jim Crow, to find success.

By Tom Lindley, For The African-American Athlete

When he was getting old enough to look at girls, Joe Clytus was warned about “reckless eyeballing,” a descriptive way of saying a black man had been caught looking too closely at a white woman.

“You were taught to survive and recognize there are things that you can do; there are things that you don’t do; and when there are things you are allowed to do, do them well,” Clytus said.

There was another reason Clytus did not engage in reckless eyeballing. He had his eyes fixed on something else – how to work his way up from the bottom of the city sanitation department and become the guy who gave the orders instead of the black guy who had to shovel manure for a white man.

In Oklahoma, as well as other parts of the country, it took almost 100 years for the Emancipation Proclamation to gain real traction. Issued by President Abraham Lincoln on Jan. 1, 1863 in the middle of the Civil War, it declared “that all persons held as slaves are, and henceforward, shall be free.”

As it turned out, their freedom did not exactly come at no cost. The University of Oklahoma, for example, did not accept black students until 1949 when a University of Oklahoma Board of Regents ruling effectively broke the unwritten law that “no Negroes remain in the university city of Norman after dark.”

The ruling was prompted by the protest of Julius Caesar Hill, a 40-year-old graduate student from Tulsa, Oklahoma who complained to OU President George Cross that his reservation for a room on the main campus had been canceled.

At the time, Norman, Oklahoma, was one of seven “Sundown Towns” in Oklahoma. If you were black, it meant what the name implied – that you better be out of town by sundown. Also on the list was Okemah, the boyhood home of Woody Guthrie, the balladeer of the down and out, whose best-known song is “This Land is Your Land.”

If you were black, you knew that was not necessarily true. Even worse, if you were as dark skinned as Joe Clytus you were viewed as inferior by both whites and light-skinned blacks.

White folks were pure. Black folks were tainted. After all, what color was angel food cake? No surprise there. Devil’s food cake? Why, it’s black.

In Clytus’ all-black school on the northeast side of Oklahoma City, you could be as dumb as a post and sit in front of the class if you were lighter in complexion. The whiter you were, the more status you had. It was part of the culture of the times.

“Kids would get on the corner and sing the song “Old Black Joe.” They were talking about me because my head was hanging low,” Clytus said.

“Gone are the days when my heart was young and gay,

Gone are my friends from the cotton fields away,

Gone from the earth to a better land I know,

I hear their gentle voices calling Old Black Joe.

Chorus:

I’m coming, I’m coming, for my head is bending low,

I hear their gentle voices calling Old Black Joe.

Why do I weep, when my heart should feel no pain?

Why do I sigh that my friends come not again?

Grieving for forms now departed long ago.

I hear their gentle voices calling Old Black Joe.

Clytus spent the rest of his life making sure “I was going to maybe work harder and maybe be smarter. I didn’t give a damn how much you yell at me or how white you are, I can deal with you. I decided that early on.”

The blacker the berry

The sweeter the jam

I don’t give a damn

How black I am.

Joseph Lee Clytus Jr., was a scrawny little kid who eventually topped out at 5-foot-7 as an adult. But he could  defend himself with his mouth and by always trying to get in the first lick, preferably on the square of someone’s nose.

defend himself with his mouth and by always trying to get in the first lick, preferably on the square of someone’s nose.

His parents lived in a small duplex at 704 Phillips, about four blocks south of the University of Oklahoma medical school campus. As part of their training, interns at the medical school delivered babies in the black community, and Clytus benefitted from their schooling. He was born at home, a dresser drawer serving as his crib for the first six months of his life.

Clytus was lucky in one sense in that his parents Joseph and Geraldine were a strong influence in his life. One of his earliest memories of his father occurred when he was about 4 years old and walked to the bus stop at 4th Street and Phillips with him the day his dad went off to fight in World War II.

“He was 27 years old and had two kids. But they drafted him into the Army,” Clytus said. “I think they wanted him as fodder for the Japanese invasion.”

His father returned safely from the war, but that didn’t change the black-and-white world in which “Little Joe” he grew up.

“You knew if you were approaching a white person on the sidewalk that you moved over,” Clytus said. “You were taught to defer because it meant survival and you took those lessons seriously if you wanted to survive.”

Another lesson Clytus learned the hard way as a child involved the police.

A bunch of kids were popping firecrackers on the corner and Little Joe had squandered about a dollar’s worth at 25 firecrackers for a dime when the police showed up.

Everybody ran except Clytus, who didn’t see them coming.

“The kids ran to my dad and said, ‘They got Little Joe.’ Well, my dad went down to the corner to get me and gave me the only spanking I ever got in my life because the police got me.

“I explained to him that I didn’t see them or I would have run like everybody else. He said that wasn’t the case.”

“You were being brave,” his father insisted.

“No, dad, I didn’t see them,” Little Joe answered.

“The point he wanted to make was that for any reason I should stay out of trouble.”

That’s not to say Joe Clytus did not grow up without convictions of his own making. He got a foothold on understanding who he was and how he wanted to behave on his first day of kindergarten.

“I was getting ready to go to school and my shoes were particularly hard to get on,” he said. “The strings were broken and there were knots in the strings. I had on high-top shoes, and when you tried to tighten the shoes the laces wouldn’t go through the holes.”

He finally got them on but when he and his sister started out the door, she said: “Your shoes are on the wrong feet.”

“I’m just going like I am,” Clytus responded. “I’m not going to struggle to get these shoes on again.”

His sister would have been ashamed to see her brother go to school that way, so she helped him get them off and back on.

“I’m grateful she did and have rewarded her many times for helping me with that. But the more important thing is I was prepared to go as I was rather than do it over. That’s happened to me throughout my life. I’m not prepared to do it twice. Do it once and do it right, and then I’m going to go.”

Something else changed his life in kindergarten.

One day his teacher pulled him up by his collar and said, “Clytus, you are a nuisance.”

“It was like, who me? What am I doing? After that, I knew that whatever I was doing I had to stop,” Clytus said.

Clytus straightened up enough to learn some Latin and become an altar boy in the neighborhood Catholic Church, although that didn’t end well, either.

“My dad was a Catholic. It was an expensive undertaking in those days,” Clytus said. “The nuns were very strict. I’m left-handed and the nuns tried to make me right-handed because all the desks were right-handed. Now, 65 years later, I don’t write well with either hand.”

Clytus went to Mass on Sunday mornings and then attended Sunday school with his friends, most of whom were Baptists. His political leanings also were influenced at an early age by a couple in the neighborhood who babysat him. A died-in-the-wool fundamentalist Christian Republican, she spoke despairingly of President Franklin Roosevelt, Clytus remembers.

They were Republican because Abraham Lincoln was a Republican, and they had known people born into slavery. They prayed on their knees every night and were like substitute parents to Clytus.

“You could say I grew up a mixed bag,” he admitted.

He also grew up in a segregated world as no blacks were allowed to live north of 8th Street in Oklahoma City until 1951, economically and socially constraining a whole section of town.

Clytus’ aunt was one of the few exceptions.

She was a bootlegger, and she had one thing hardly any other people of color had at the time – cash money and a lot of it.

One source of income was a juke box that was positioned squarely in her living room. Not far away at her kitchen table, her customers liked to down corn liquor by the one-ounce shot.

Frequently, someone at the table would hand Clytus a nickel to play a song on the juke box.

His aunt also gave him his first lesson in commerce by paying him a quarter for every clear short half-pint liquor bottle I brought her. She then would take the bottle and fill it with her homemade corn liquor and pass it off as premium bourbon, fetching her a much higher price than she could get for her home brew.

“White lightning corn liquor is clear, so she would turn liquor into bourbon by putting a tea bag in a half gallon of corn liquor and letting it sit until sundown,” Clytus said. “If you were a sport, you’d drink the ‘bourbon’ because the point was that somebody saw you drinking it. It was all about appearance.”

Clytus lived only two blocks from Deep Deuce (the black entertainment district) and would comb the alley every Saturday morning looking for good bottles to sell to his aunt.

He also learned a few lessons in life hanging around his aunt’s house.

It was not a big secret what line of work she was in, which occasionally brought the sheriff to her door.

“The sheriff would come down to visit her liquor joint and say, ‘Roxie, you know I’ve been good to you. Can you help me because the election is coming?’” Clytus recalled.

And, as their arrangement called for, she helped get out the black vote.

To ensure her enthusiastic support, the sheriff would occasionally bust her liquor joint. It also was a way for him to demonstrate that he was tough on crime.

“Roxie, we are going to have to take you down,” the sheriff would say.

“You know I’m not going down there (to jail).”

She would then call her husband “Big Jim,” who hung out at another bootlegger’s house, with the news that the sheriff was there. Big Jim would come home, climb in the front seat of the patrol car and went downtown. A couple of hours later he was back home, minus the money it took to pay his fine.

With his ringside seat, Clytus learned something about how politics was played in those days. Looking back at his aunt’s relationship with the sheriff, he has concluded there were worse places for a black man to grow up than Oklahoma City. “I realized that Oklahoma City is a generous place,” he says. “Maybe that was because some of the pioneers were still around when I grew up. I also believe it was easier for black people to vote here than it was in other parts of the South. I don’t remember a time my parents didn’t vote.” While he never felt constrained by overt oppression, it was something that his parents always reminded him that caused him to want to pursue his own destiny.

“Most of the help you will ever get as at the end of your wrists,” they told him.

The one thing he wanted most of all early in his life was to attend YMCA summer camp in the Arbuckle Mountains. Few black children were lucky enough to have that opportunity, and camp was certainly too much money for his parents to cough up. So Little Joe decided to pay for it himself. He delivered the morning and afternoon newspaper and washed dishes at Adair Cafeteria. He also saved his lunch money for a whole school year. When he had what he needed, he told his parents he was going to go to camp.

Clytus liked the taste of freedom, and by the time he started attending all-black Douglas High School, he was sharing the sidewalks with white people, whether they were ready or not for him to be there.

First of all, times were changing, and second, he got exposed to being around kids from all-white Northwest Classen High School when students from the two schools worked on science and biology projects at the University of Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

He also found time to get his girlfriend pregnant his senior year in high school. There wasn’t any question about what to do next. They got married and have been together 55 years.

“Everybody thought it would last six months,” he said.

Clytus also was accepted at the University of Oklahoma in 1959, only nine years after the first black student was enrolled.

Being accepted and being able to afford to attend were two different matters, however.

“I was married and had a child and I didn’t know how or what to do,” he said. “I was working and washing dishes at Val Gene’s, a restaurant in Penn Square, when someone said Bill Jennings (the president of Penn Square Bank) was having a party and needed someone to work the bar.

“I said sure, I will do it. I get in my old car and go to his house in Nichols Hills, where the bar is set up in a little back bedroom. “Suddenly, I’m the bartender. The problem is I don’t know the difference between gin and vodka, and I’ve got no place to pour my mistakes. So I drink them because I don’t want the man to know I’m

wasting his whiskey.”

After five or six mistakes, Clytus got up the nerve to pull out an acceptance letter he had received that day from OU and show it to the crowd, which brought a round of applause from what by now was a fairly cheerful bunch.

His tips suddenly started mounting and when Clytus got home and cleaned out his pockets, he was $75 richer. He made enough money that night to pay for a whole semester of tuition at OU.

“I was bursting with pride,” Clytus said.

His good fortune was only temporary as Clytus, who wanted to major in pre-med, dropped out after a year and a half.

“I found out how hard it was, and I was struggling to pay for it,” he said.

Here he was, a young black man with a wife, child and only a high school degree from the wrong side of town to show for his efforts.

He got a job with the city, picking up trash around Lake Hefner. It paid minimum wage, $1.14 an hour. His wife started ironing shirts for a penny and a half a piece at the laundry. On a good day, she made $9.

“We were on our own, struggling, but we were intent on making a life for ourselves. What choice did we have?”

That’s why Clytus didn’t think twice the day he was transferred to the city waste treatment plant and realized that his job was to shovel manure in the bottom of a 10-foot deep concrete vessel.

He was the first black man to work at the plant, and the odor wasn’t the only shit he had to put up with. His white co-workers, who were up top, initiated him by dropping wrenches on his head as he was at the bottom battling manure.

Clytus decided he wanted more out of life.

“Who’s the boss of this whole place?” he shouted out one day from the bottom of the hole he was trying to dig himself out of.

They told him the city manager was in charge.

“I think that’s what I will be,” he concluded.

Not long after that, Clytus put on his best and only suit, shined his shoes and crashed the City Manager’s Christmas party in downtown Oklahoma City. When Clytus saw the man get on an elevator, he ran to get in it before the doors closed. He introduced himself and told the City Manager all he needed was an opportunity. The City Manager made note of one Joe Clytus, who eventually became a lab technician at the waste treatment plant, assistant city manager and budget directorfor the city of Oklahoma City.

“It took hard work, smart work,” he said. “I knew that if I was going to get a fair shake with a white person I had to be smarter than they were and I had to be better and to work harder.”

His dad told him to be careful not to beat them by much, else they might resent him and make life more miserable for him.

So he practiced a lot of patience and persistence.

His first big break came in 1964 in the middle of a campaign to convince voters to approve an issuance of bonds to build a new wastewater treatment plant.

“They had opened I-35 and everybody who passed through Oklahoma City smelled the old plant,” Clytus recounted. “The big boss came down to the plant and said, ‘Joe Clytus, we need your help.’

“Every day, they had me report to the Chamber of Commerce, which was running the bond campaign, and he told me they would tell me what to do. Every day, I’d go there, put on my best slacks and sports shirt and shine my shoes. Then, I would go door to door and hand out a flyer, and tell people that I worked at the waste treatment plant and that we were trying to fix the smell. Enough of the black community voted for it to help get it passed.”

The city manager asked Joe how he could repay him, to which Clytus said: “Give me a promotion.”

He went from lab tech to chemist and eventually to superintendent of wastewater. In the process, he attended night school, earning an associate degree from Oklahoma State University technical school in 1970.

In 1969, he had read an advertisement recruiting applicants for a National Urban Fellowship, paid for by Ford Foundation.

One of the requirements was to have a bachelor’s degree, which Clytus had yet to earn. But he applied anyway, and was accepted with the provision that he complete his undergraduate education before the fellowship ended.“I believe I got accepted because most other black people were in housing, social services or personnel, and I’m a guy who works in a real live necessary city function with an associate’s degree in civil engineering,” Clytus said.

At the age of 29 with a wife and three children at home, Clytus went to Yale University to begin his fellowship and on to Tacoma, Washington, to start his internship. At night, he attended Pacific Lutheran College in Tacoma to pile up more credits.

He also got started on completing his bachelor’s degree with the help of a professor at Oklahoma City University, who was drawn to Clytus’ story.

“I met Mac McCoy, who was a professor of business, and showed him the letter that I had been accepted as a National Urban Fellow and that they would pay $50 a credit hour for me to work on a bachelor’s degree. I said, ‘Can you help me?’”

McCoy signed Clytus up to finish his degree at OCU in a most unconventional manner.

“He gave me a stack of books to read and said when I came back in December they would give me a four-hour test and send the results to Princeton University to see how many hours of credit they would give me.

“Well, I finished the summer at Yale, finished the internship at Tacoma, went to night school at Pacific Lutheran and came back to OCU around Christmas and took a four-hour exam. I finished it and got 20 hours off college credit.”

He repeated the process again and at the end of the next semester received another 20 hours of credit. The date on his bachelor’s degree from OCU reads: July 7, 1971. The date on his master’s degree reads: Aug. 15, 1971.

“I’m proud of that story,” he acknowledged.

Upon completion of his degree, Clytus was appointed assistant to the city manager and became a problem solver for the administration, finally retiring in 1978 as budget and personnel director to pursue other business interests.

“When I was budget director, I was watching the money, watching the money and I see there’s a lot of it going out the door to contractors, so I said I think I will retire, get my net up and catch some of this money.”

He went into business for himself: cleaning and televising sewers. Yes, he was back in the sewer but this time the manure smelled more like money because in order to qualify for grants from the Environmental Protection Agency to construct wastewater treatment plants, applicants had to document how much extraneous water that required further treatment was getting into the system.

“It was called an infiltration and inflow study and I started a company to do it,” Clytus said.

He didn’t have the $65,000 he needed to get started, so he went to the bank, where a black loan officer turned him down, even though Clytus was putting up $15,000 of his own money.

“The president of the bank was Joe Simrod, and when I ran into him later at a party, I said I needed to borrow some money and told him what I needed it for. He said to go see his assistant, Fred Moses, and tell him what I needed in order to get some government contracts to do the work.”

Clytus volunteered to mortgage his house but Moses said no. He didn’t even want a mortgage on the truck Clytus needed to buy to do the job.

“We believe you are going to pay us back,” Moses said.

Clytus repaid the loan within six months.

“It’s not like I did this alone,” Clytus emphasized. “I did this with help. But I understood how to acquire help because I was taught as a kid to be honest, be forthright and work hard.”

He bought a 67,000-pound truck and a high-pressure hose that would clean and evaluate the condition of the entire sewer line. Clytus had a television camera mounted on the end of the line and pulled it through the sewer, too, allowing him to take a picture of the sewer and put it on tape so if down the road the sewer broke road the sewer department could determine where the break was.”

He formed a partnership with another man andmonitored and cleaned sewers all over the country before selling the business to a company on the New York Stock Exchange.

Clytus later did consulting and marketing work for a large wastewater treatment company and bought a check-cashing business before turning most of his attention to improving conditions in the African American community.

“Hometown Boy Makes Good.” That was the headline in the newspaper when Clytus he received the National Urban Fellowship, which was formed to train minorities in public administration.

“One of the things that happen when a hometown boy makes good is that a lot of folks in this town said, ‘Let’s help him out. He’s doing the right things that we are preaching about.”

So Clytus got help from the banker, contracts to read water meters and clean sewers and run wastewater plants, mainly because he was doing the things society had taught him – white society.

“Society says if you do all of that stuff – keep your nose clean and get a good education – you will succeed in America. Usually, that didn’t work for black folks, but I believed it.”

And he wanted to give back, so he got elected to the Oklahoma City school board. That experience drew a blunt assessment of what’s wrong with public education.

“What I discovered was that there never had been an elected official in the state who didn’t love schools. They loved them so much that they would always pass a law so they could say they loved schools. But after a while, there are so many laws that the system becomes dysfunctional.”

Clytus was born at 704 Phillips and now lives at 50th and Lincoln, about four miles away. He drives the same streets, frustrated when he sees the city cutting weeds on empty lots that were once homes to black families before Urban Renewal forced them off.

“We tore down the black community and we tore down downtown businesses and 40 years later we are doing everything we can to bring it back,” he said. “But when I look back on it, I can say I have applied a lot I learned as a child. That’s what I’ve done.”

It’s not where you start, it’s where you end up.

(What happens when you find something worth fighting for and refuse to let go of it no matter how tough things get? That’s the premise behind “Opening Doors” by author and journalist Tom Lindley, who captures the stories of 13 Oklahomans who found a way to open their own door in life.

They range from an African-American high school student with a pregnant girlfriend who rose to a position of significant responsibility in municipal government, to a gay man in a highly prejudiced state who became a respected politician to an African -American woman from a family of 15 children who became a Metropolitan opera star. Collectively, they demonstrate the exceedingly important fact that success comes in many colors, with the green of money being the least important. “Opening Doors” reflects Lindley’s interest in sharing the inspirational stories seemingly everyday people have unknowingly scripted for themselves.

Lindley is the former editor of The Flint Journal.

The book was published by Full Circle Press. You may contact the Full Circle Bookstore at 405-842-2900 for a copy.)