Notice: Undefined offset: 1 in /var/www/wp-content/themes/jnews/class/ContentTag.php on line 86

Notice: Undefined offset: 1 in /var/www/wp-content/themes/jnews/class/ContentTag.php on line 86

By Roscoe Nance, For TheAfricanAmericanAthlete.com

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]lcorn State basketball is a mere afterthought these days. The Braves finished the 2018-19 with a 10-21 record, and have only had a winning record twice in the last 20 seasons. But there was a time not too long ago when Alcorn State basketball was a force.

And they let the world know it, too.

But 40 years ago last month, Alcorn had the college basketball world buzzing and were the

toast of the town among HBCUs.

Led by future NBA stalwart Larry “Mr. Mean’’ Smith, they were one of only of two unbeaten teams in the nation – Larry Bird’s Indiana State squad that lost to Magic Johnson and Michigan State in the NCAA Finals was the other –

with a 27-0 record.

Of greater significance was their 80-78 upset of Mississippi State on March 9 in the first round of the NIT before their season ended with a four-point loss to Indiana in the second round.

“It was exciting times for Alcorn and Mississippi,’’ explained Lonnie Walker, Coach Davey “The Whiz” Whitney’ assistant during the Braves’ halcyon days. “Some of the things we did people did not think we could do.’’

The Alcorn-Mississippi State contest made history because it was the first time any of Mississippi’s three major universities – Mississippi State, Ole Miss, and Southern Mississippi – played a predominantly black school within the state.

Fans gobbled up 10,000 tickets in the first six hours after they went on sale. The game was supposed to be

a walkover for Mississippi State. The Bulldogs had finished fifth in the SEC with an 11-7

conference record and 19-8 overall.

They were led by their frontcourt of Rickey Brown, a 6-foot-10 center, and Wiley Peck, a rugged 6-7 forward, both of whom went on to play in the NBA.

Alcorn was a deep, talented team. Four its five starters – Larry Smith, Alfredo Monroe,

Ronnie Smith and Pee Wee Horton – averaged double figures scoring as did sharp-

shooting sixth man, Joe Jenkins.

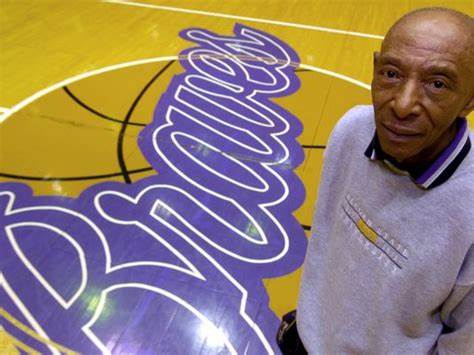

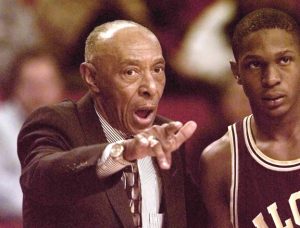

The diminutive Whitney, a one-time shortstop for the Kansas City in the Negro League who succeeded Ernie Banks when Banks signed with the Chicago Cubs, had a penchant for wearing his lucky brown suit for big games

and smoking ‘Lucky Strikes’ cigarettes, was a master of man-to-man pressure defense and fast break

offense.

He used an eight-man rotation – forward Cornelius “Stick’’ Jenkins was the fifth

starter and guard E. J. Bell and forward Bill Howard came off the bench – to wear down

opponents and rack up victories.

The Braves out-rebounded opponents by 15 boards a game, No. 1 in the nation; they

outscored their foes by 14.8 points a game, fifth-best in the country; their 93.8 points a

game were second only to the Runnin’ Rebels of UNLV and limited the opposition to

.435 shooting from the field, No. 15 in the country.

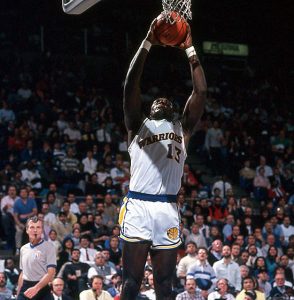

Team leader Larry Smith, who played 13 seasons in the NBA with Golden State, Houston, and San Antonio was No. 6 in

rebounding at 13.7 a game and No. 18 in field goal percentage at .606. Smith was the Braves top scorer with 17.7 points a game.

But the Braves were not very highly regarded outside of HBCU circle in spite of their perfect record and gaudy stats.

The NCAA Selection Committee thumbed its nose at the Braves when it picked its 40-team field. The SWAC champion didn’t receive an automatic berth in those days, and the committee didn’t deem the Braves worthy of inclusion.

However, the NIT thought differently and paired them against Mississippi State. But there was a catch. NIT Executive Director Peter Carlesimo and his cronies made the Braves the road team for the March 9 contest despite their superior record instead of, at a minimum, scheduling the game for a neutral site such as the Mississippi Memorial Coliseum in Jackson. It’s a move that still rankles Smith.

“We should have played them on a neutral court,’’ he says. “Unfortunately during that time, that wasn’t going to happen. We were unbeaten and had to go up to there house.’’

That said, the Braves didn’t lack for confidence when they boarded the bus and headed up the Natchez Trace to Starkville.

“Our confidence came from a combination of things,’’ Smith says. “Coming to Alcorn, most of our guys had come from winning programs. All we knew was to win. It was unusual to get a group of guys like that together.

“We knew how to win. Winning pretty much was all we knew. Losing for us at the time was not an option. It carried over from there. It was what we believed in and the confidence we had in each other that we could

get it done.’’

In the end, it didn’t matter where the game was played as Smith sank a short jumper for the game-winner as

time expired, after retrieving a loose ball in the paint. The play had been called for Joe Jenkins, Alcorn’s sharp-shooting sixth-man to take the last shot.

But the Bulldogs took away that option. Center Alfredo Monroe ended up with the ball. His was partially

deflected but still got up to the rim. Smith then did what he did best. He corralled the ball and put it back up in one motion for an improbable 80-78 victory.

“I was fortunate enough to be in the area,’’ he says. “My initial reaction was time running

out and I had to shoot it. When I shot it, I knew it was good.’’

The shot left Mississippi State’s fans and team members stunned. The Bulldogs had led

by 16 points in the first half and by as many as 11 and 10 in the second half.

Brown had doubled as a cheerleader when Mississippi State had the lead, pumping his fist in the air as

ran upcourt following each Bulldog bucket. In a cruel twist of fate, the ball ended up in his

hands following Smith’s decisive basket.

Brown gazed at the ball briefly, as if looking into the eyes of a lover who had betrayed him, flung it toward the ceiling of Humphrey Coliseum and fell to the floor.

The Braves used pressure defense and a fast break offense – their staples the entire

season – to fashion their comeback. They got an assist from the Bulldogs, who were lured

into playing at the Braves’ pace despite the protestations of their coach, Jim Hatfield.

Point guard Tom Schuberth, who transferred from UNLV and had lettered on the Runnin’ Rebels’ 1977 Final Four squad, was accustomed to playing an up and down game and reverted to what he knew best.

“He wanted to run,’’ says Walker, “and they had won some games off pushing the ball

because those big boys (Brown and Peck) could run the floor. He fell right in our hands.

We had been running all year.’’

Alcorn’s scouting report said Peck and Brown couldn’t handle the ball. With that in mind

Whitney threw a variety of presses at the Bulldogs that kept their guards from getting the

ball and forced Peck and Brown to try and it across the timeline.

Alcorn’s cat-quick backcourt players Pee Wee Horton, Ronnie Smith and E. J. Brown picked their pockets

repeatedly, the Braves only trailed 37-31 at the half.

Mississippi State regrouped in the second half and was on top 73-63 with four minutes

left in the game. But the Braves, a veteran team made up mostly of juniors and seniors,

didn’t crack.

“Our guys would not panic,’’ Smith says. “We had been down before. We had time. We

just hadn’t played well. We had time to redeem ourselves. The thing I can say about our

guys is we didn’t fear them. That’s why we didn’t panic. We felt we had time to get back

in the game.’’

The Braves had plenty of reason to believe they could pull the game out. After all, they

had been in much more dire situations during the regular season. They rallied from eight points behind with 1:23 to

play to beat SWAC foe Southern University in overtime on the road.

Alcorn tied the score at 74-74 with 2:11 remaining. Alcorn took a 78-76 lead on a steal

by Smith with 1:23 left. Brown countered with a 15-foot jumper with seconds on the

clock, and overtime seemed to be a certainty until Smith settled the issue.

“We had been in those games before,’’ Smith says. “We were a tough-minded team. We

were a disciplined team. We had the pieces in place to beat them. Being unbeaten and going into their place. We felt we were a better team. Any of our guys could have started.

“That’s what separated us from those other teams,” he added. “Another thing we did that was a

little different from other teams. We played all the time. In the off-season, we would play games. It was a year-round thing for us as a team. That made us unique.

“And we had tremendous leaders. When you have those people in place that are going to push you, and

once you put all the work in and see the reward at the end, it makes it more worthwhile.’’

The Braves’ victory against Mississippi State shocked the basketball world. A bunch of ragamuffins from the SWAC weren’t supposed to beat an SEC squad — no way, no how, no time.

The skeptics obviously had never heard the Alcorn cheer that said, “Who dat?

Who dat? Who dat talkin’ ‘bout beatin’ dem Braves? Who dat?’’

That went for Mississippi State as well as the Braves’ SWAC opponents.

“We felt we were a better team,’’ Smith says. “We felt we matched up with anybody in

the country, across the board. We were deeper than a lot of teams. That’s how we felt as a

team.

“We didn’t go into that detail (about the historical significance of the game). We

knew about being the first this and the first that. People were letting us know that. We

didn’t let that distract us.

“We knew they could only put five on the floor just like us.’’

The victory kept Alcorn’s unbeaten season intact, but the ramifications were much

greater. Braves guard Ronnie Smith probably summed it up best when he said

immediately after the contest, “

“It’s like when the man walked on the moon. It’s one small step for Alcorn, and one giant

step for all black colleges.’’

Alcorn’s reward for its historic victory was a second-round game against Indiana on the

Hoosiers’ floor five days later.

Indiana, two years removed from winning the NCAA title,

finished fifth in the rugged Big Ten and boasted four future NBA player – guards Mike

Woodson, Butch Carter and Randy Wittman and forward Ray Tolbert – and legendary coach Bob Knight

“Indiana was different type ball club,’’ Walker says.

And 17,222-seat Assembly Hall was a different type of venue. It took four years to build at

of cost $26.6 million and had opened seven years earlier when Knight arrived. School

officials wanted the majority of seats on the sides to improve fans’ viewing experience;

so in order to accommodate more than 17,000 seats in the arena the needed to be very

steep. That caused crowd noise to rain down onto the floor.

“When we walked in there, all we saw was red,’’ Walker says, “We had played in that

kind of setting before but not like that. We had maybe 10 people. The noise was

cascading down on the floor. We couldn’t say some of the things we wanted to say (to the

team) because fans were screaming so loud.’’

The noise forced Whitney to move the team huddle during timeouts from the bench area onto the court; the move only helped a little.

“That was a good experience,’’ Smith says. “Over the years we had always been a road team (12 of Alcorn’s 27 regular season games that season were on the road). If you go back through our games, we only played a small number of games at home and those were mostly conference games.

“We were comfortable playing at other people’s venue. We weren’t all shook up because we had to go and play at other people’s place. It became the norm for us. It was a beautiful sight. We had never played in a venue that size and that

many people. It was unique.’’

Alcorn played Indiana on virtually even terms before losing by four points, and Knight was

complimentary of the Braves performance

“Make no mistake. They had a good team,’’ Smith says. “I felt some of the calls didn’t go

our way. I’m not saying that because we lost the game. We made plays and the whistle

was blown late.

“Them being at home they were going to get the home cooking. They’re

going to get the calls. The calls were a little different, some questionable Make no

mistake, at the end of the day they were a good team. That’s how it goes sometimes.

“Going in they knew we would be a hard team to beat. There weren’t any surprises. They

knew we weren’t going to be a pushover team. They knew they had to bring their A game

to beat us. That being said, we were coming to play. We felt confident. We took it as it

was just another game and we had to do what we had to do. We earned their respect.’’

The Braves also earned the respect of the basketball world.

The following season they earned an at-large berth in the NCAA Tournament and defeated South Alabama in the

first round to become the first HBCU win a tournament game. They lost to LSU in the

second round.

“I think about all the things we did, the accomplishments,’’ Smith says. “The team we

had accomplished a lot of things, opened the door for a lot of folks, made things a lot

better and showed people that coming from a small school we could compete with the elite teams.