Notice: Undefined offset: 1 in /var/www/wp-content/themes/jnews/class/ContentTag.php on line 86

Notice: Undefined offset: 1 in /var/www/wp-content/themes/jnews/class/ContentTag.php on line 86

By Roscoe Nance, For TheAfricanAmericanAthlete.com

February 13 isn’t generally considered a special day. It’s the day before Saint Valentine’s Day, but that’s no big deal. It is also the day that Eddie G. Robinson was born 100 years ago (1919) this year, and in Black College Football circles that should make it a very special day.

Coach Rob _ as he was affectionately known throughout his legendary 56-year career at Grambling State – did more to elevate the level of respectability of Black College football and introduce it to the masses than anyone else in the history of the game.

He did things no other coach had done. He was the first to crack the 400-win mark; his teams were the first to play a game outside the continental United States. In the mid-1970s only two schools had nationally syndicated coach’s playback show. Notre Dame was one. The Grambling Hi-Lite Show was the other.

But there was much more to Coach Rob than winning a lot of football games and developing scores of pro football fields. He touched lives and molded men in ways unlike any football coach before or after him.

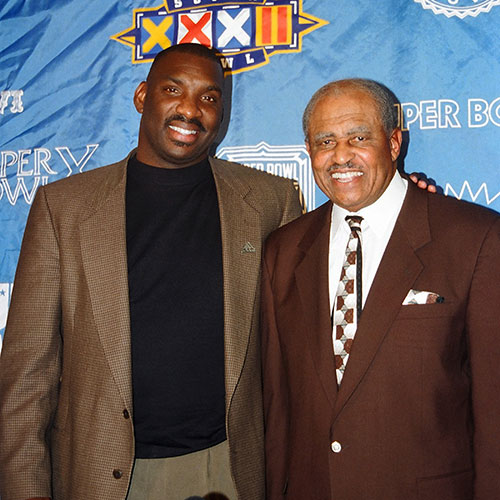

“No one can explain Eddie Robinson, ’’ says Doug Williams, the first Black quarterback to win a Super Bowl, MVP of Super Bowl XXII and probably the best known of the athletes who played for Robinson. “Coach Rob was bigger than a coach. He was a mentor. He was a father. He was a psychologist. He was a provider. Coach Rob made sure as a young Black man you understood what it was going to take to go out in life in America and be successful. Those are the things he preached every day. After practice, it wasn’t about practice, it wasn’t about the Xs and O’s. It was about how you handle yourself on campus; it was about how not to treat women; it was about going to class; it was about going to church; it was about, graduating and being a good American.’’

Coach was born the son of a sharecropper and a domestic worker 100 years ago on Feb. 13. His parents divorced when he was in elementary school. Common thinking says he would have become a statistic, another Black youngster beaten down by the odds. But common thinking didn’t apply to him and didn’t want it to apply to the athletes who played for him.

“I consider him a drum major for humanity,’’ said Wilbert Ellis, the Associate Athletic Director at Grambling. “He reminds me of Martin Luther King. He was concerned about humanity and making a difference in people’s lives, especially youth.”

He would say, ‘We have to get ‘em, but we have to do more with ’em than just get ’em. We have to develop ‘em so they can be men of great character so they can go out and represent not only their family and the University, they can represent all.

Their light will shine so until people will say, ‘He must be a G-Man because of his dress, his appearance, the way he speaks and the way he carries himself. He was a football coach but he believed in doing something beyond football.’’

Coach Rob didn’t play favorites with his players. He loved to say “Everybody is somebody at Grambling.’’ That was not just a slogan with him. It was heartfelt, and it showed in the way he coached his team. He was as concerned about the third-string left tackle as he was the All-American quarterback, often saying, ‘’You can’t coach ‘em if you don’t love ‘em.’’.

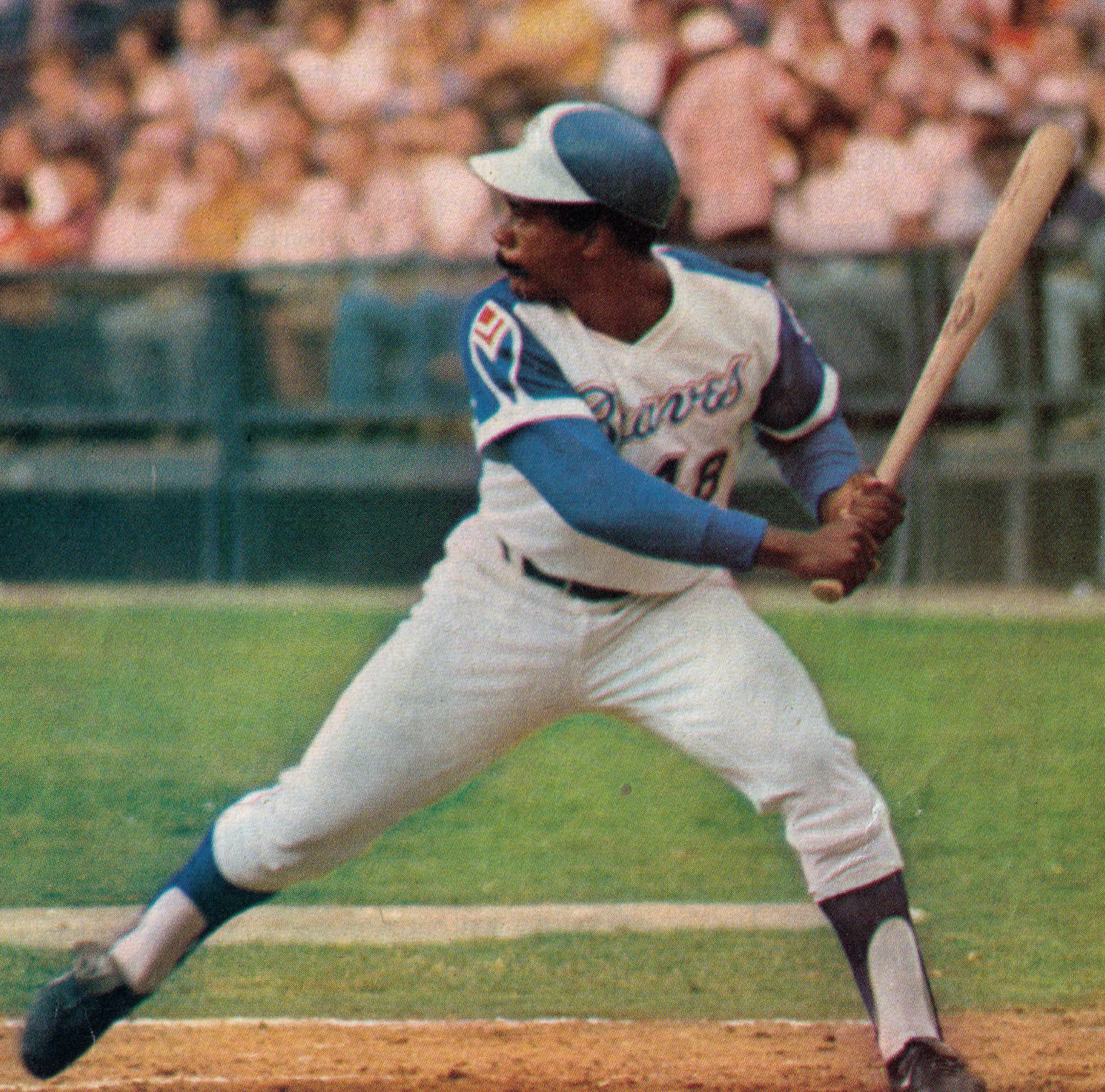

He took as much pride in having former players who went on to become doctors, lawyers, teachers, college presidents, and just everyday husbands and fathers who provided for their families as he did in the Buck Buchanans and Willie Browns and Charlie Joiners and Everson Walls who are enshrined in various halls of fame.

When they were at Grambling he treated them all the same. That, in his words, meant “coaching them like they were the boy that you wanted your daughter to marry.’’

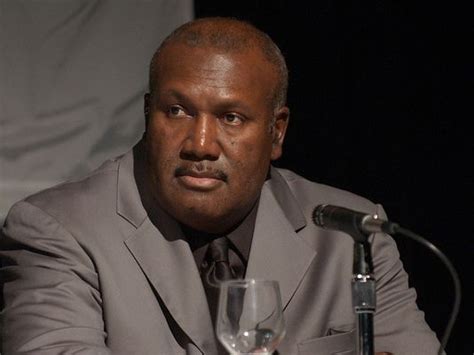

“Coach Robinson represents that man your parents wanted you to be when you were growing up,’’ says Black College Football Hall of Fame co-founder James “Shack’’ Harris, who was the first Black quarterback to open an NFL as the starter. “He was more than a coach, more than a man. He was kind of like a trustee of life. He was more unique than anybody I ever met. It’s fashionable for coaches to say how much they care about grades when it’s truly about winning football games.

“It’s fashionable for coaches to say they’re concerned about players beyond playing. Coach Robinson helped so many players beyond playing. He helped so many guys get jobs. He truly did believe in you becoming the best player you could be and leaving there with a college degree. He promised your parents when he was recruiting you that you would get a degree, go to church and you would leave there prepared for life.’’

Coach Rob used unorthodox methods to keep his promise to parents. He would personally go through the dormitory ringing a cowbell at 6:30 a.m. every morning waking up his athletes and collecting their meal cards. That was his way of ensuring that they would go to class. The only way they got their meal cards back was going to the dining hall for breakfast and retrieving them. Robinson figured if the athletes had to get up to go to breakfast, they were more apt to go to class.

“Nobody else was doing that,’’ says Ellis. “We don’t have that too much anymore. That’s why we’re in the condition we’re in many instances. People are only trying to get out of them what they want.’’

Coach Rob took athletes from small towns and rural areas in Louisiana and across the South and showed them a side of life they likely never imagined through football. One of his mottos was “The stadiums of the world are Grambling’s home’’ and he schedule games in nearly every major city in America, in addition to playing in Tokyo twice.

“I don’t know if I ever would have gone to New York if it hadn’t been Grambling,’’ Williams says. “My first plane ride was to New York with Grambling.

“I got a chance to go to Tokyo twice, to go to Hawaii twice, to play all over the country. Coach Rob afforded me that opportunity.’’

For Coach Rob, it wasn’t enough for his teams to travel all over the country. He made sure team members knew proper etiquette when they arrived at their destination. He and his wife Doris showed them the proper way to sit at the dinner table and which utensils to use. He required them to wear a coat and tie when they traveled. If they didn’t know how to tie a tie, he taught them.

“He didn’t play that pants sagging off your behind or wearing tennis shoes,’’ Williams says. “You had to wear shoes; you had to wear button-down shirts, a tie. You had to wear a coat.’’

Coach Rob rose to the top of his profession through determination, hard work, and sheer willpower and doing whatever had to be done to make his program successful. In the early years, besides coaching the team, lined the field, drove the team bus and wrote game stories for the local newspaper.

He often said “a man’s only limitation is his imagination.’’ He used his imagination to build Grambling into a powerhouse with national name recognition that rivaled Southern Cal, Alabama, Michigan and any of the other so-called big-time programs.

Yet he carried himself with humility while demanding that his teams “lose with dignity and win without acting the fool.’’ He was always accessible to the media. If a reporter wanted to interview him, all he had to do was call directory assistance to ask for his number. Whenever he spoke in public, he made sure to thank the media for coming out.

“He was very media savvy,’’ says Black College Football Hall of Fame broadcaster Charlie Neal. “Collie Nicholson (Grambling’s long-time Sports of Information Director and the mastermind of the Grambling Hi-Lite Show) helped mold that image. He understood the benefit of looking good through the media. That’s why he was able to garner so much respect from the coaching community and the nation as a whole.’’